Jorge Diezma / El florero en flor / R.J.B.M / 15.09 - 19.11 / 2017

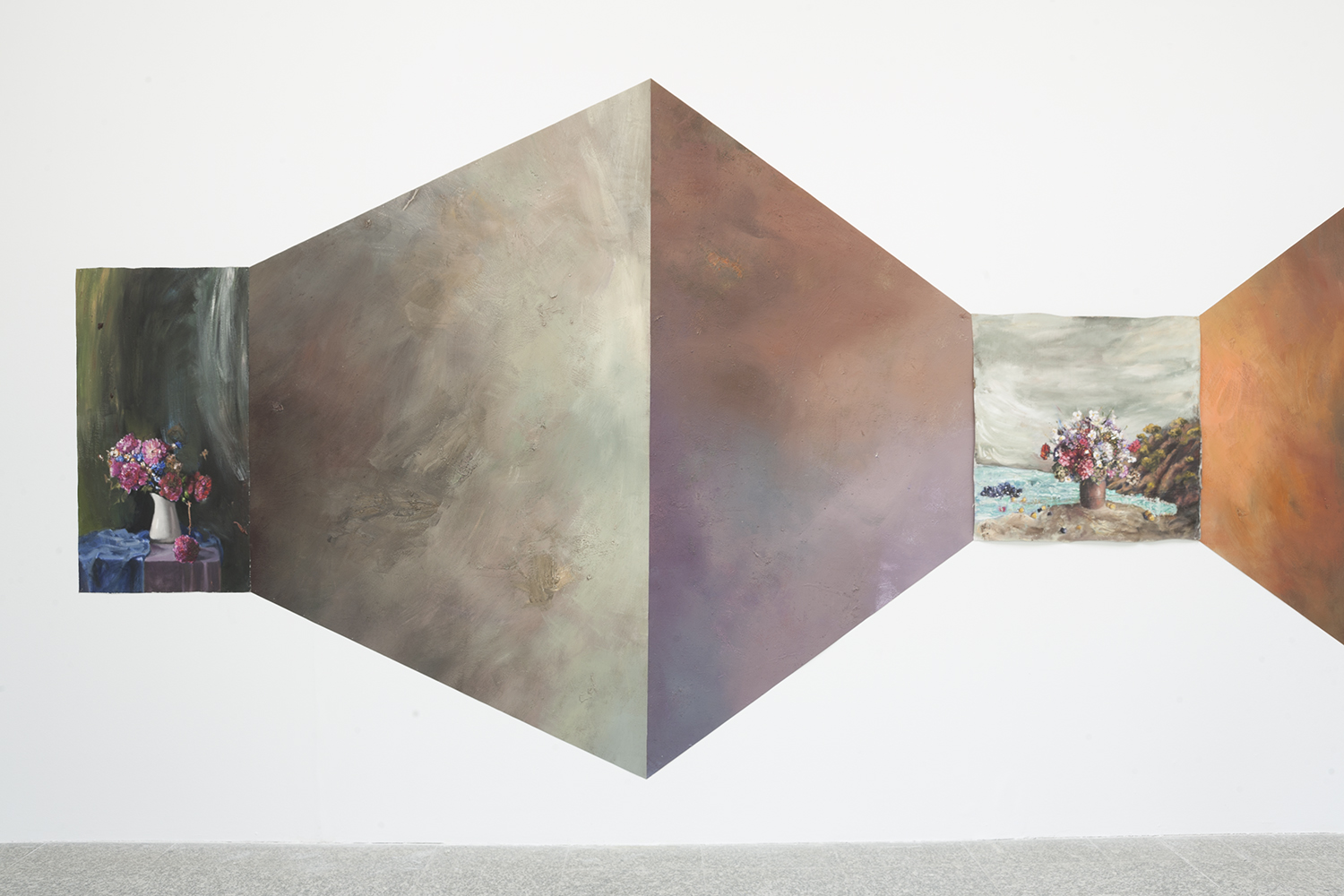

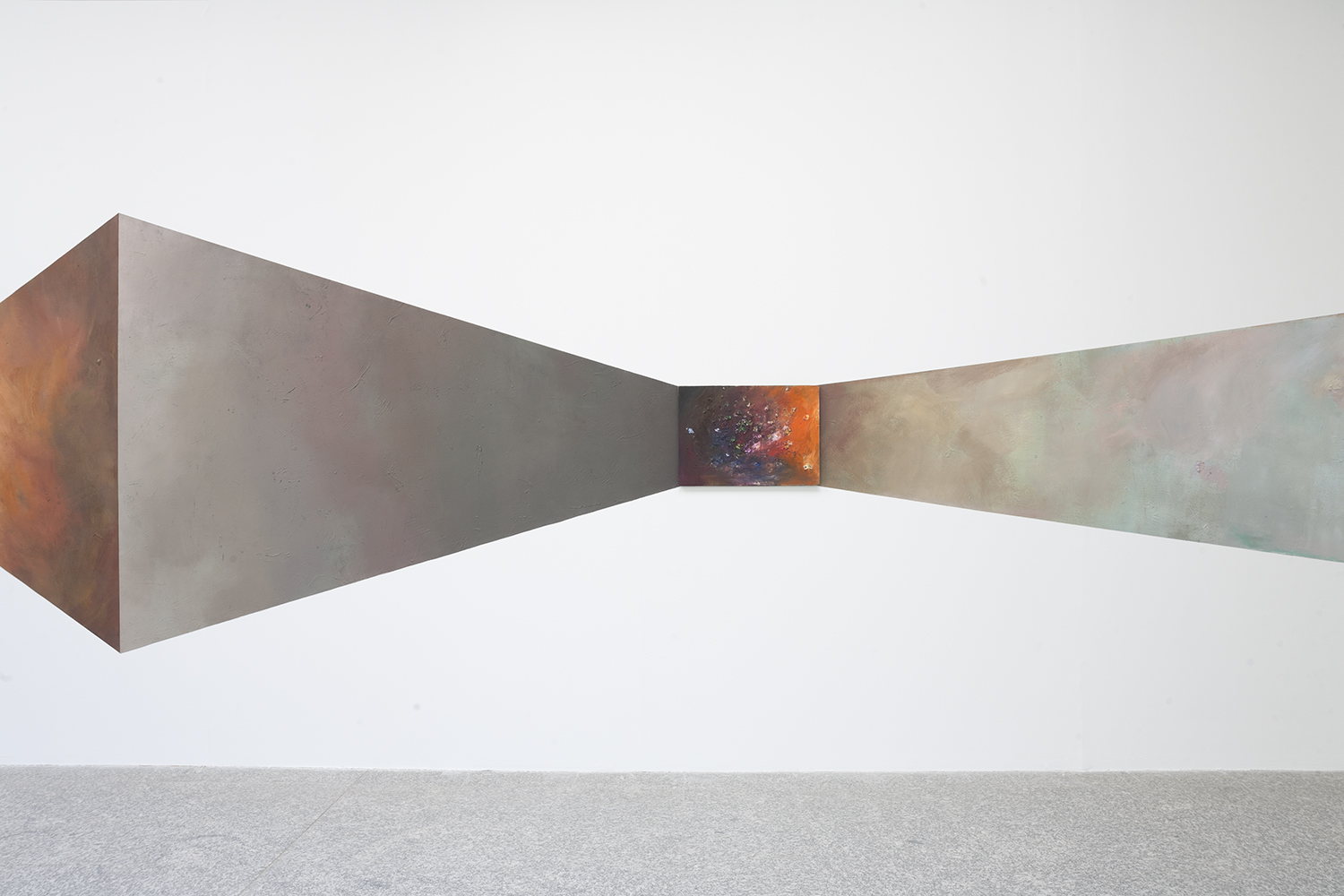

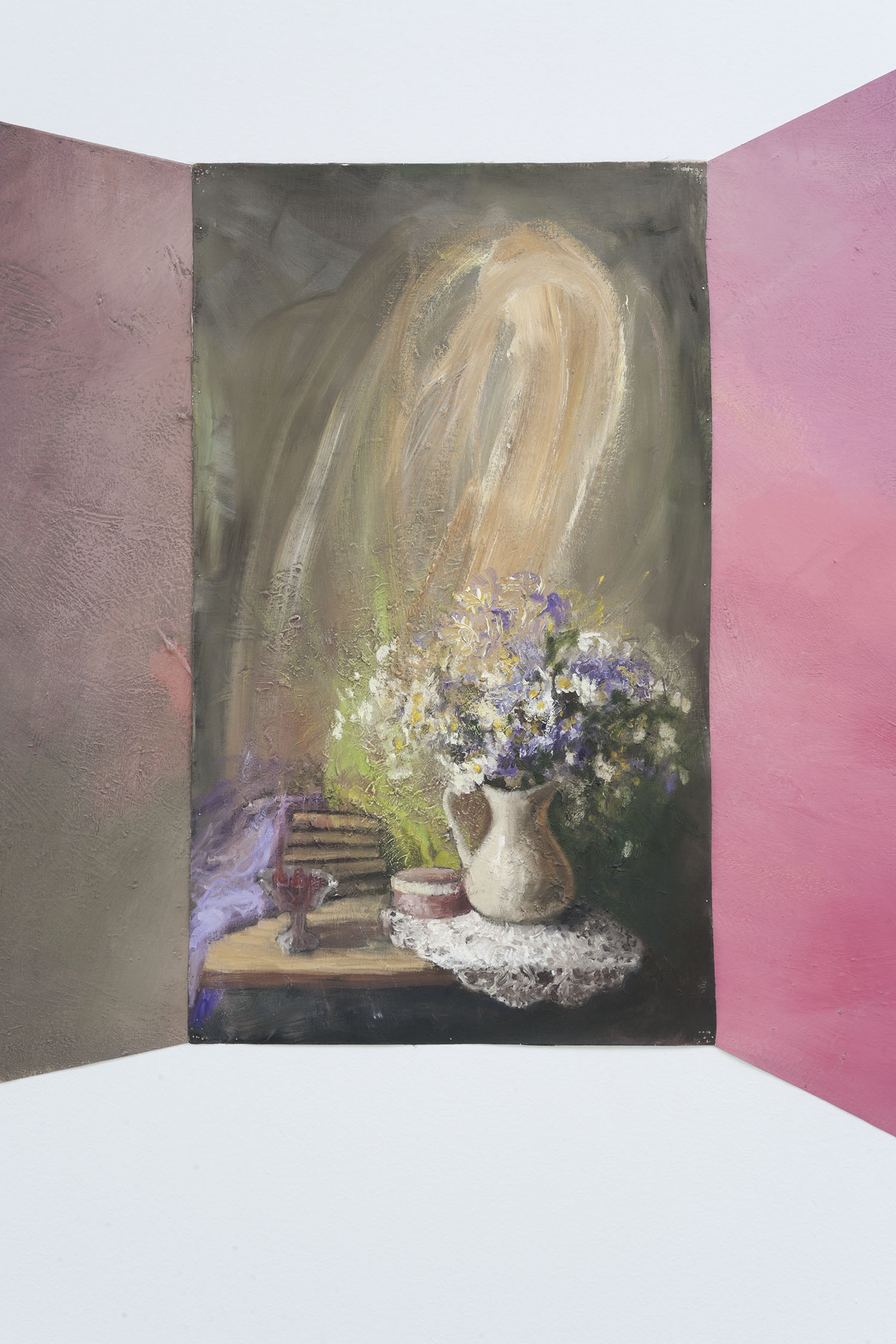

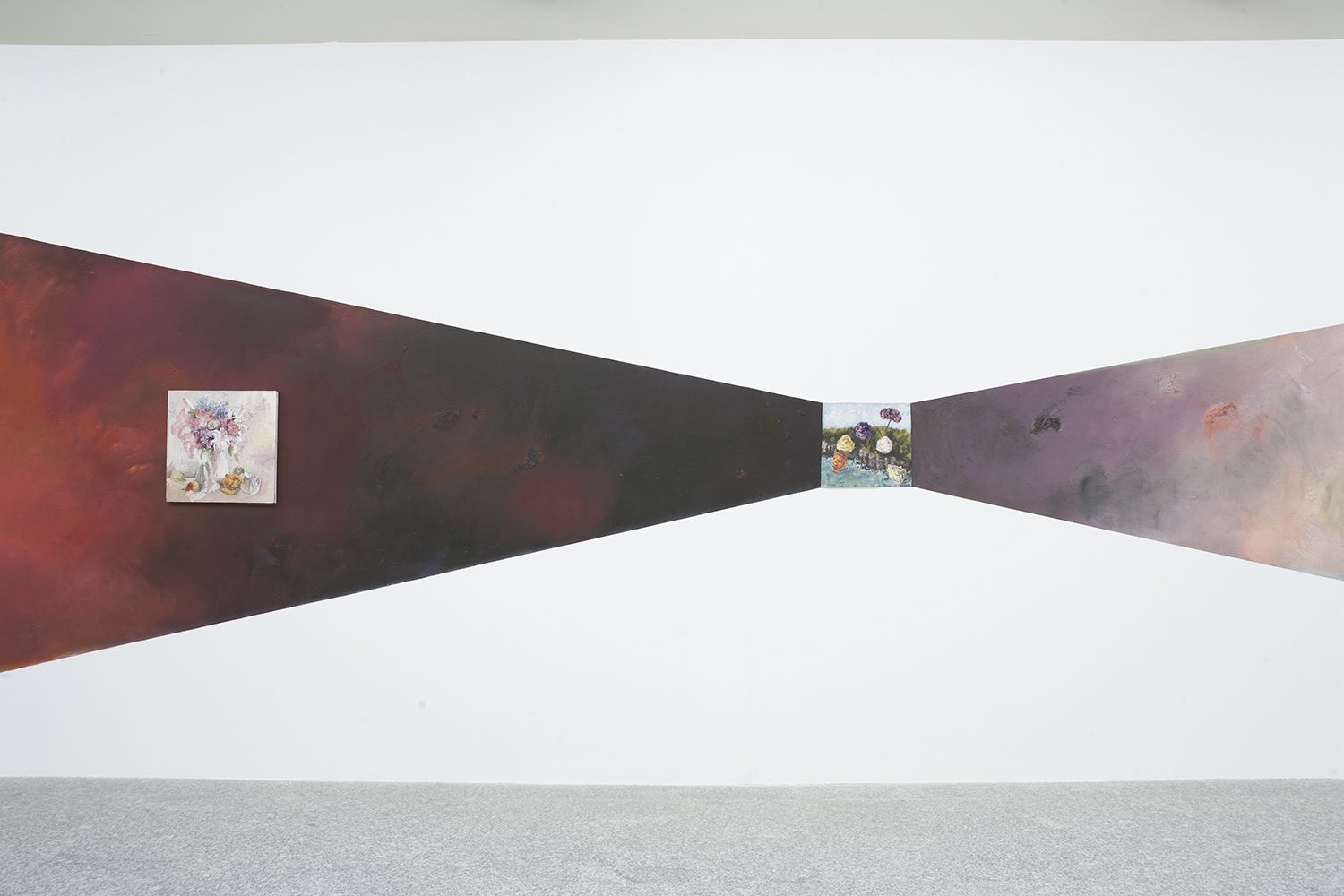

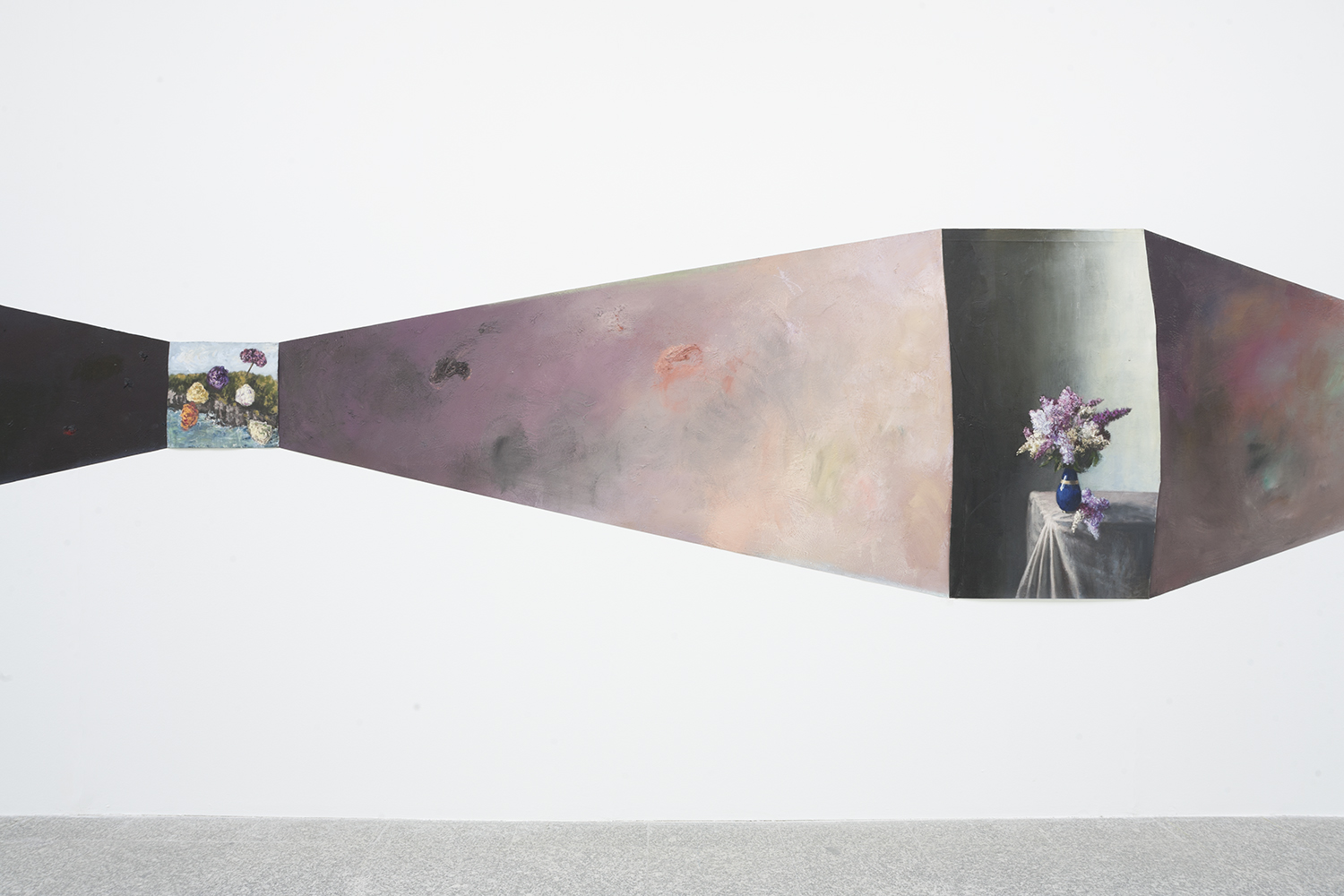

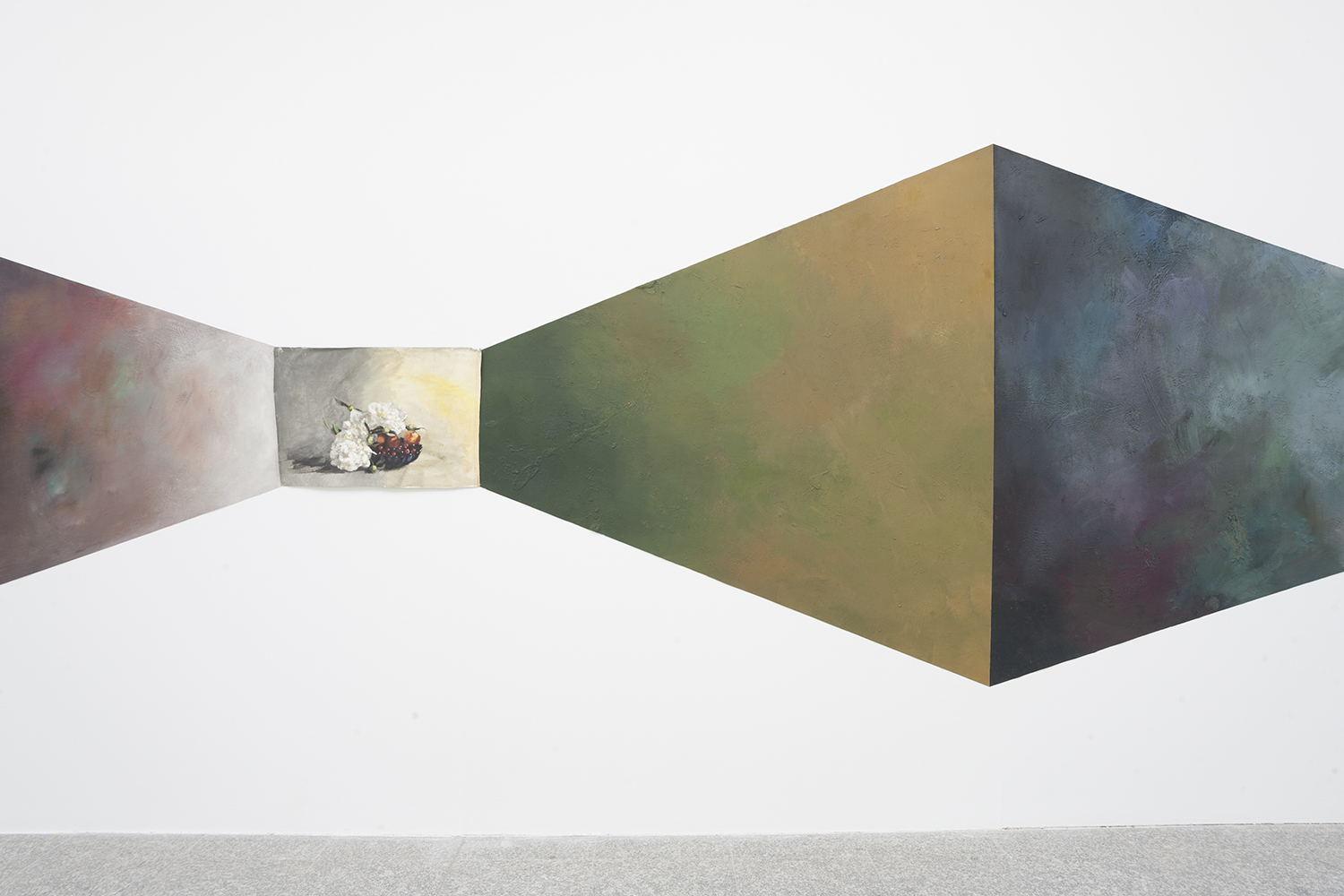

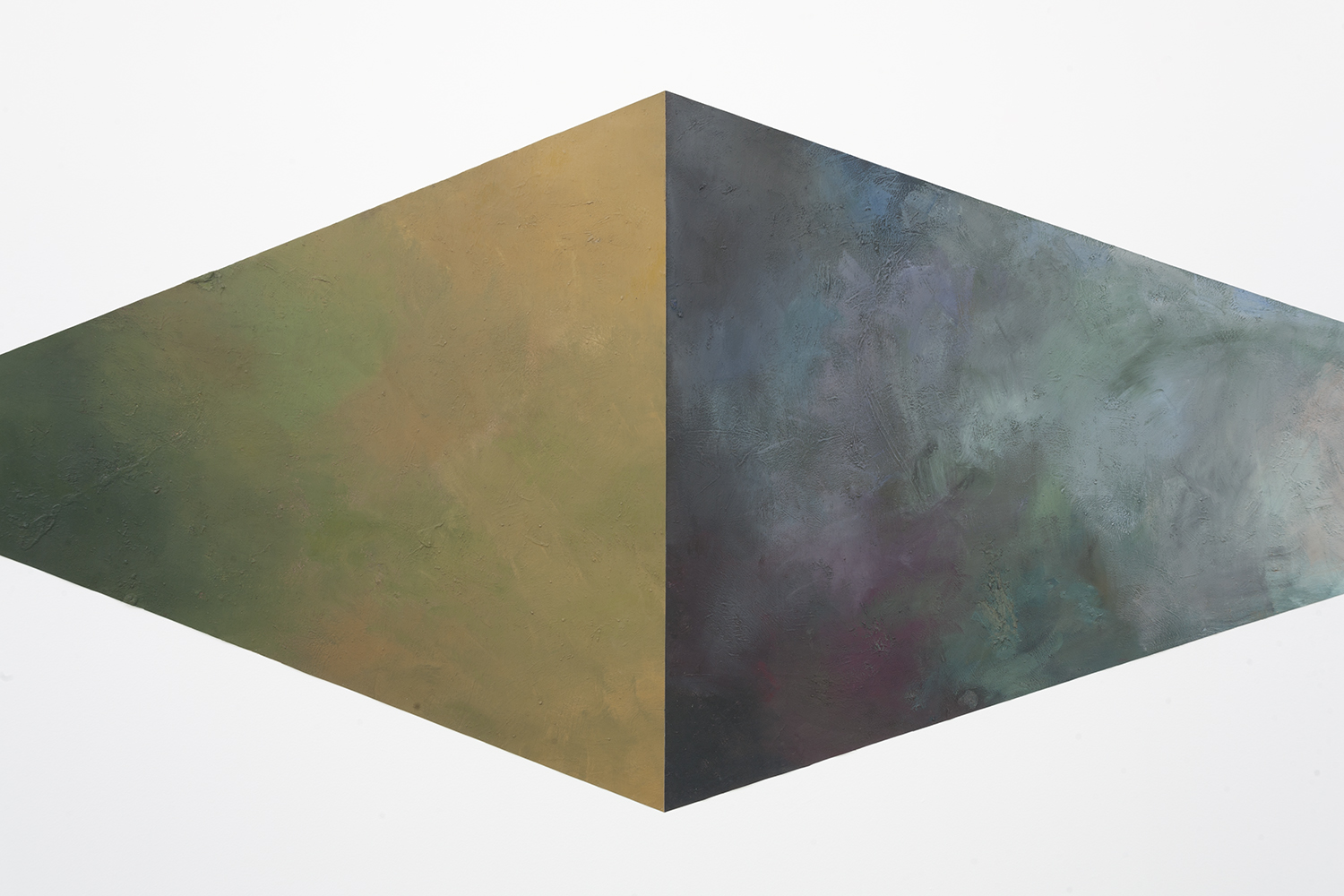

Jorge Diezma's exhibition at the Botanical Gardens presents still-life paintings of flower vases that point us to the bourgeois tradition, though executed in a style that gives knowing nods to amateur and genre painting, alongside other abstract and colourful paintings which, in this display, serve as a link and loudspeaker for paintings of flowers. These canvases of colour, which we might (cautiously) term ‘abstract', call to mind, in their size and hard-edge, certain Minimalist artworks, such as a number of pieces by Sol LeWitt or Ellsworth Kelly. Despite their cold outline, however, these canvases painted using many overlaid strata of oil paint generate a texture rich in reverberations of colour and rough impasto; recognisable and somewhat romantic sweeps of the brush - without going quite as far as gesturality - that seem to wish to invite us to appreciate the mere pictorial matter as we make our way from one painting of flowers to another. The piece could be compared with a subway line, with the flowers as the stops and the geometries as the journeys between them.

In these paintings of flowers, it possible to identify another connection, one slightly more deeply buried, with a certain avant-garde genre of painting. The still life was a motif repeatedly used by painters in the early 20th century and, if we look back, we can see there is no ism that did not find in it a good basis for its expression. Bearing in mind that the still life was at the very bottom of the classic hierarchy of genres that held sway up until the 19th century, one might infer that there is a subversive aspect to the choice of the still life as a subject for avant-garde paintings. What artists were doing in such works was challenging the very idea of a hierarchy, understood as a sort of stairway with steps that rise from the insignificant to the sublime. Painting in the early 20th century brought the good and the bad together in the same canvas, thenceforth forcing opposites into a strange contiguity, opposites that till then aesthetics had been bent upon keeping as far apart as possible. The paintings by Derain or Renoir in his latter days are good examples of this cohabitation, but if there is one recurrent pictorial reference for Diezma in recent years, then it is the Italian painter Filippo de Pisis, in whose work painting without any value whatsoever and painting of incalculable value are done using the same brush in a strangely simultaneous manner.

Such a mélange brought with it an entire set of new problems: if the bad and the good are now presented to us together, how are we going to be able to distinguish them? The answer was the rise of criticism, which became essential as a means to establish the value of new works, while at the same time the external signs that indicated that we were looking at an important piece multiplied. The small, tacky work painted impulsively and carelessly on a cheap, cracked canvas demanded a vast white wall, which in turn required a distinctive, immaculate building. In this way, with the passing of time, some of these paintings that were both good and bad were simply endorsed as good. How else could the market value of a work be established or a comprehensible history of art be told? However, if we look closely at many of those paintings again, or virtually any painting produced since then, we can see that they are still good and bad at the same time, and it is fascinating (and sometimes frustrating too) to perceive how opposites cohabit in a tightly interwoven intimacy that is impossible to undo.

What Jorge Diezma suggests in this exhibition is precisely that we halt to look at the paintings just at the moment prior to putting them in their place.