Breza Cecchini / I Wild, Yes / 06.05 - 08.07 / 2023

According to Mircea Eliade, the horse is a chthonic and funerary animal. In Cirlot's dictionary of symbols, he notes that dreaming about a white horse is, in some cultures, an omen of death. Jean Clair emphasises the horse's character as a psychopomp, upon discovering the backdrop that Picasso designed for the ballet Parade. However, in a beautiful scene from On the Road, Jack Kerouac describes how Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty come across a white horse in the middle of the night, in the woodland where they'd parked their car. The scene speaks to us about the intensity, in all its fleetingness, of freedom. Breza Cecchini Ríu (1976) was brought up among horses, in a family of riders, and she can still see the animals, every day, from a window in her house. Her painting speaks to that same freedom and intensity. Horses are an essential motif in her paintings, and they appear with ambiguity and ambivalence; they evoke the compelling darkness of fairy tales, of dreams and their hidden meanings, and of the portents of tarot.

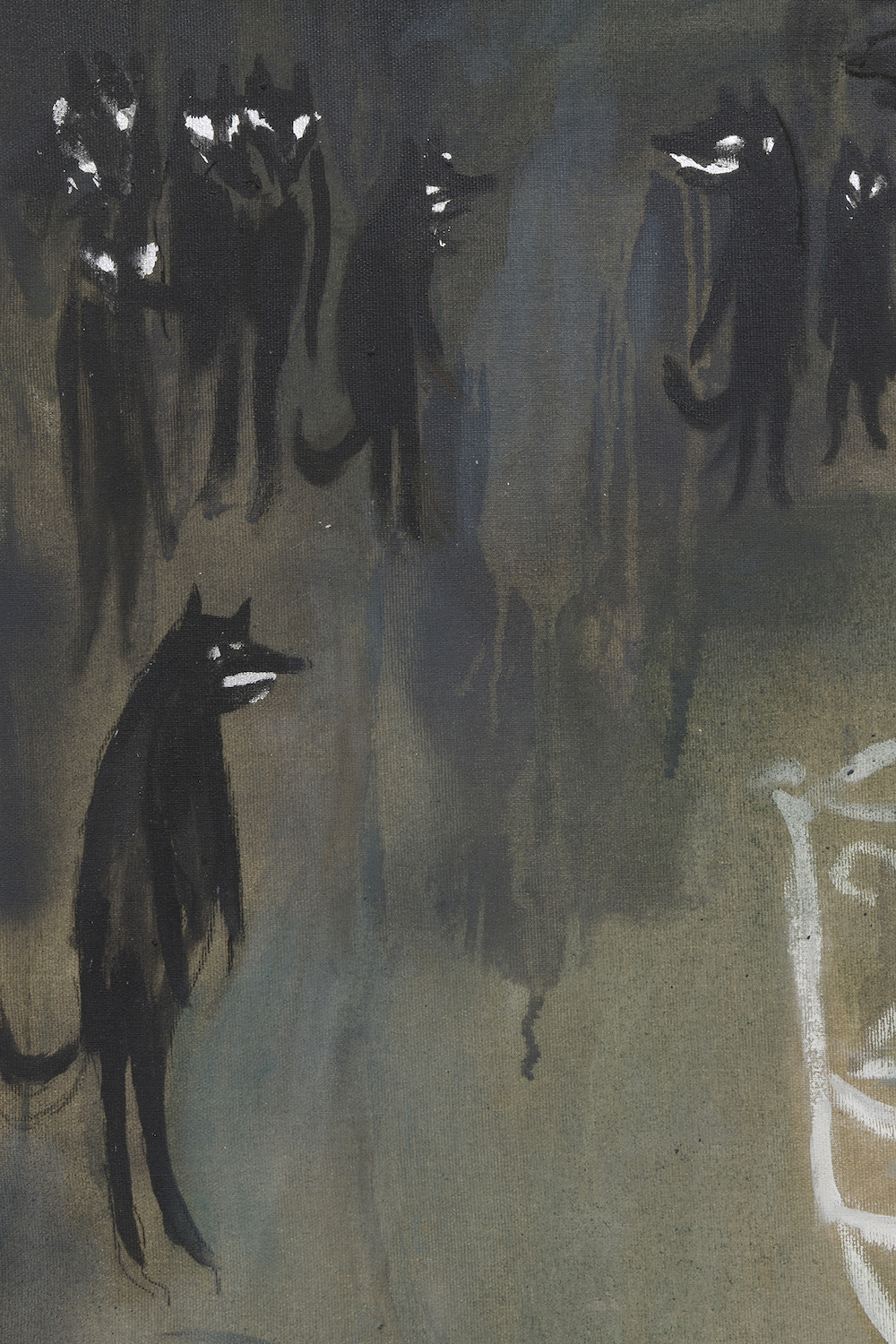

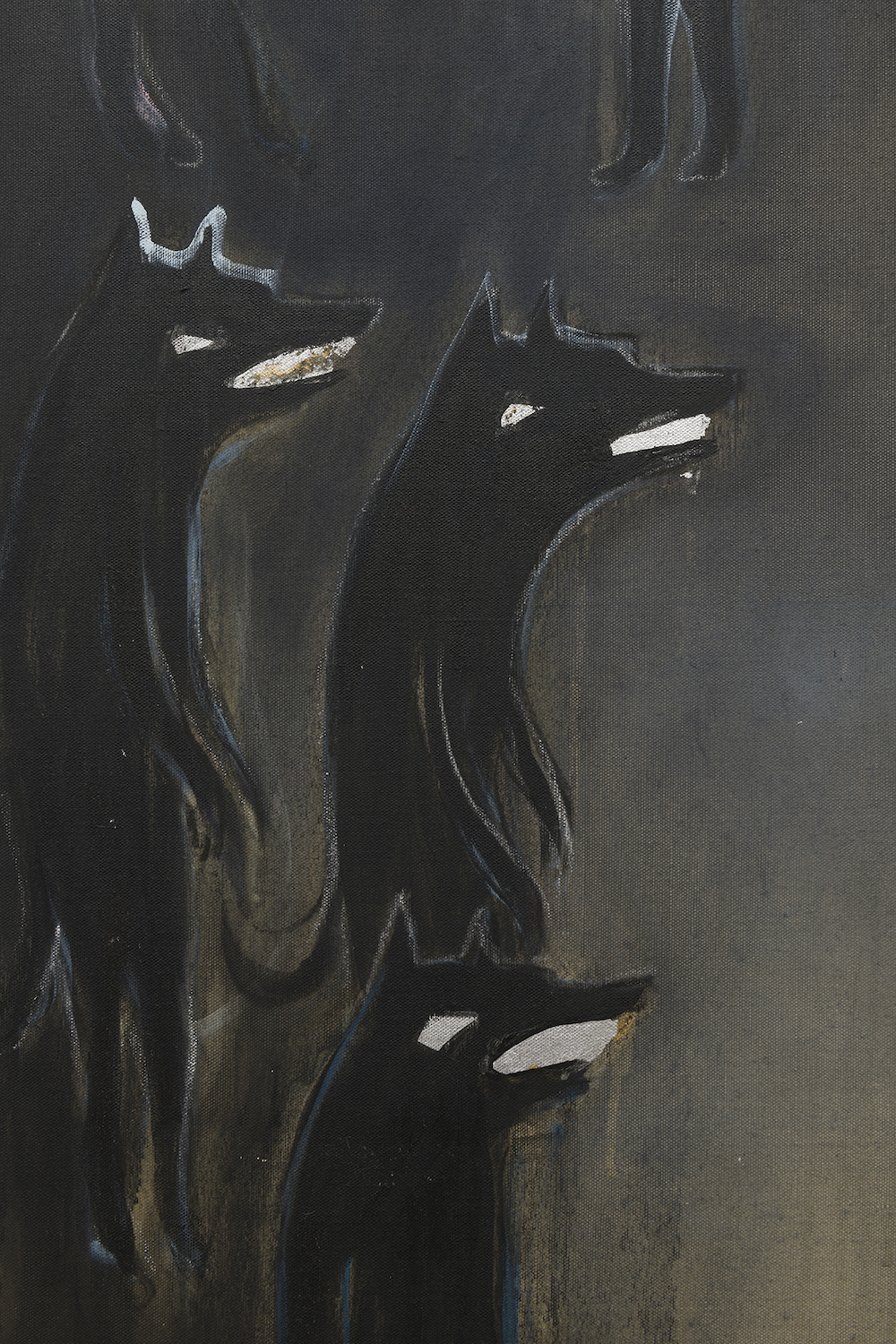

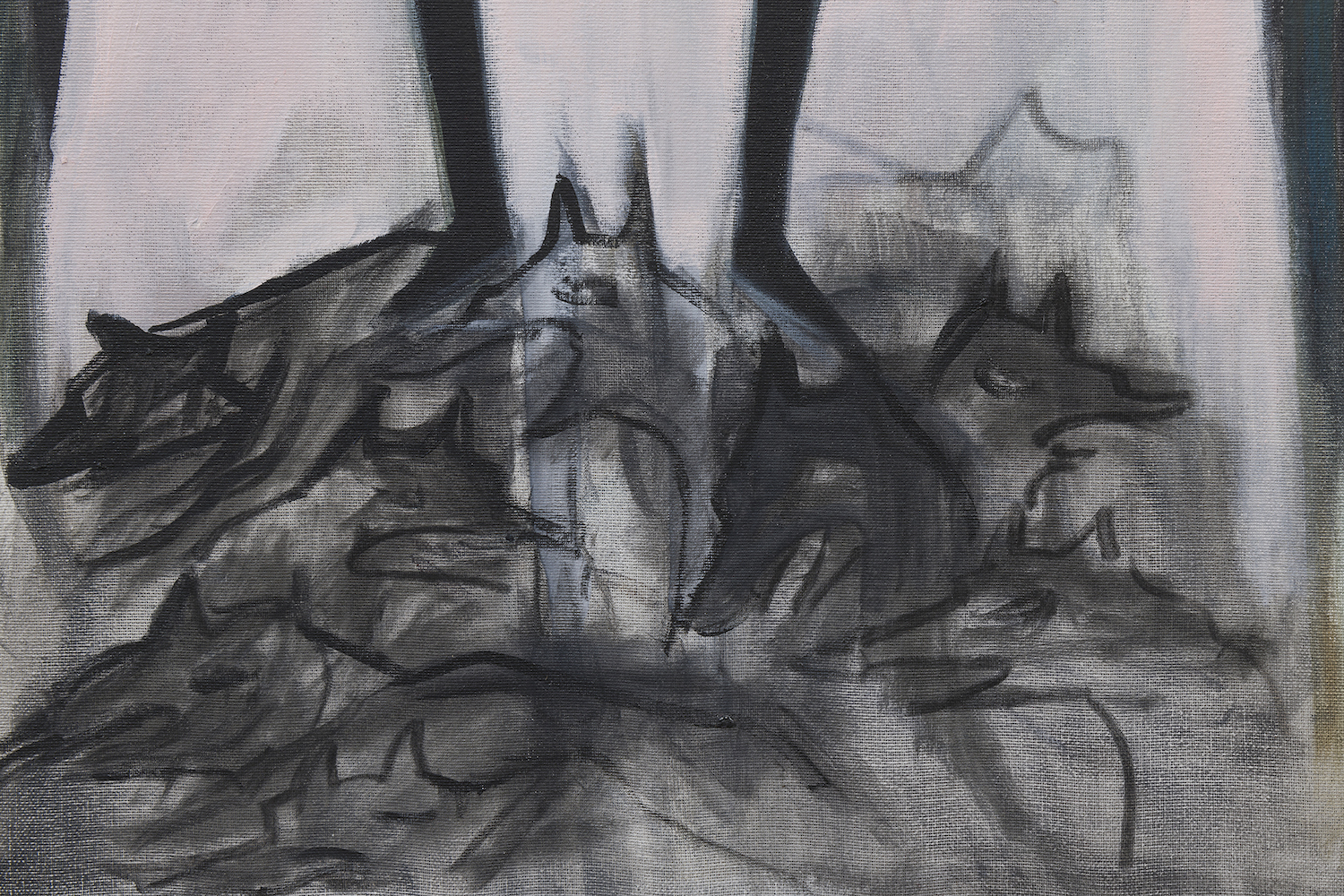

In Nordic mythology, the wolf Fenris devours the sun at the culmination of the Twilight of the Gods. Long before then, the Greeks spoke of Lycaon, king of Arcadia, whom Zeus turned into a wolf for having served him human flesh at a banquet. For Walter Burkert, this story echoes the masculine ferocity and guilt of the early stages in humans' transition from gatherer to hunter. In children's imaginary, the figure of the wolf is still a detestable predator, something sinister and dangerous. Nevertheless, in a marginal part of Christian iconography, Saint Christopher - the saint who comforts and protects souls on their different journeys - was depicted as a cynocephalus until the Middle Ages. Wolves also feature in Cecchini's painting, as memories of past menaces, but also as allies, guides and protectors. Wolves and horses come together in the figure of Little Red Riding Hood, who swaps her cape for the red dress coat of horse riders. It is a personal, highly specific game, and so masterfully articulated by the Asturian painter.

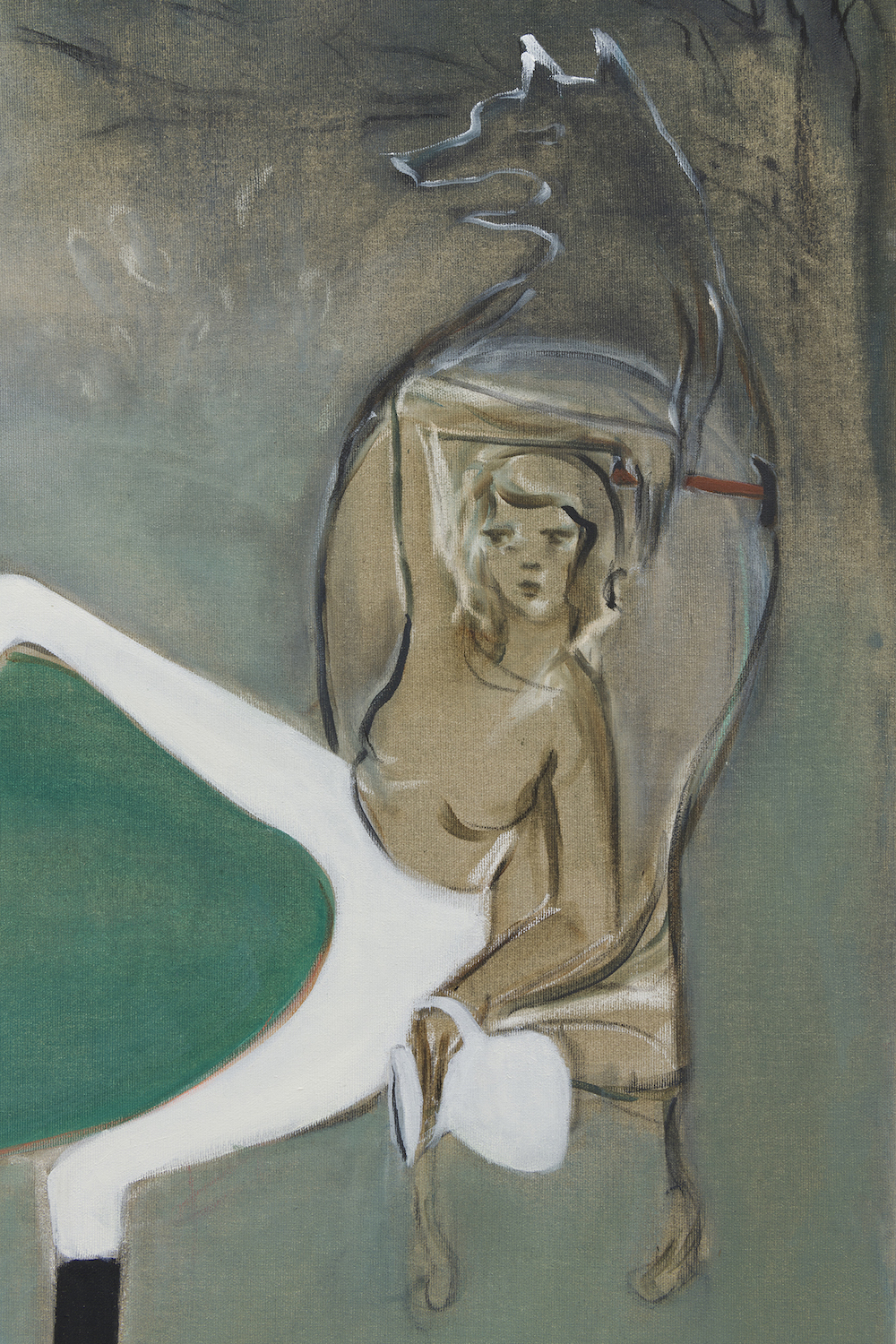

This is the iconography deployed by Breza Cecchini Ríu in I wild, Yes, the artist's first solo exhibition at Galería Alegría, in which there is also a distant echo of Molly Bloom's Soliloquy. In this exhibition, wolves, horses and women live together, as if they were jointly guarding this dream-like vision of life, creation and destruction. The artist handles the language of fantasy and folklore with great skill, delicateness and control, and she leads us into a world that is placid, albeit only in appearance. This is a symbolic, contradictory and fertile universe. Cecchini offers an open-ended imaginary, and there is no single, unambiguous interpretation; it is shot through with the primal urge to cross limits and go beyond the very edges of civilisation.

In this world, the women - whom Cecchini in fact positions at the centre of her compositions - are free, with all the entailing consequences. These are savage and meditative women who sometimes tame the animals, and at other times use them as food in their return to the abyss. This is, therefore, highly personal artwork, which the artist herself describes as a tool for exploration, a game of divination and a record of her own lived history.

This polysemy, which is so present in the work of Breza Cecchini, is perhaps what gives her painting an almost supernatural appeal and force. It seems to transcend what it represents, penetrating the spectator's subconscious, by using its veil of apparent sweetness as a ruse. Cecchini's realm is a strange one, in which night animals herald freedom and joy. The painter's unique terrain is located somewhere beyond the city walls: spectators must venture deep within it if they are to pick up the thread of a story with no beginning or end, or to discover the contradictory setting of such mystery.