Enrique Radigales / Eyetracking /21.01- 24.03/ 2023

According to Wikipedia (that digital space for settling any and all kinds of doubts), technological somnambulism is the notion that we, as a society, are "sleepwalking in our mediations with technology", i.e. that we are ignorant to the way it is changing humanity. The term was coined (and I am fascinated by the fact that the word for inventing or naming a new idea or theory also means to manufacture money) by the American political scientist Langdon Winner, and is used frequently in the philosophy of technology.

This widespread ignorance about the processes of technological change and development is partly due to the normalisation and automatisation of the use of technology in everyday life, both in terms of the devices we use all the time, and also with regards to the social activity of different areas in the political, cultural or economic system. In the day-to-day, the incorporation of advanced technologies is becoming essential, unquestionable and unconscious. Technology, just like nature, is now an area that man must adapt to. Only when it stops working do we become truly aware of the implications of this shift.

We can see this process in action today: ordinary citizens are never actually asked whether they want or need a faster/smarter/newer phone or computer. It is therefore clear, at the individual level, that the current social pact about technology does not respond to real needs; instead, new tech is an industrial-capitalist imposition, with dark implications for the state's control over citizens. What is most disturbing is that, in theory, this imposition is based (or sold) on the Enlightenment ideal that progress itself is something that keeps getting better and better, in a never-ending upward trajectory.

Some of the earliest developments in the Industrial Revolution can be traced back to the outskirts of Barcelona, along with the dawns of tech-capitalism and the disturbingly close relationship between corporate endeavours and state control. Barcelona also saw the first social and popular rejection of all this upheaval.

For Enrique Radigales, these facts bring back vivid memories of his time in the city. He lived in Barcelona from 1990 to 1995, in the Plaza de Vicenç Martorell, near Calle Tallers, which had been home to one of the first steam-powered factories in Spain. The owner of the factory had travelled to England to learn about and buy the modern machinery that made industrialised manufacturing possible. However, this experiment in technocapitalism would only last one year: the factory was destroyed in an attack by Luddites.

This time, Wikipedia (the Spanish version) informs us that "the Luddite movement was spearheaded by 19th-century English textile workers, who protested from 1811 to 1816 about the new machines that were threatening to put people out of work. The fear was that the industrial looms and spinning frames, introduced during the Industrial Revolution, could lead to the skilled textile artisans being replaced by lesser-qualified and lower-paid workers." This was long before today's so-called technological somnambulism, back when the Spanish porto-proletariat was still very much awake and alert.

Radigales would have known about this history while he was studying painting at the Escola Massana. These were his Barcelona years; he had been born in Zaragoza, in a close-knit family atmosphere very much connected to rural heritage and the natural cycles of the countryside, before he moved to the big city to study painting. The final year of his course, in the printmaking class, was when he first came across the use of computer-aided technology as a tool for artistic production. He subsequently signed up for a post-grad course in Multimedia, at the Universidad Politécnica de Catalunya.

This was when all the elements that would go on to define his artistic work, both technically and conceptually, began to emerge: the manual and the artisanal and the technological, the natural and the artificial, speed and slowness, the countryside and the city, the traditional and the brand-new... From this point on, his work was based on opposing terms that overlap or contradict or are superimposed upon each other, until structures for their coexistence eventually began to emerge.

The Industrial Revolution is accused of having destroyed both time and nature. That is, it destroyed the time used by the artisan to produce his work, while nature was sacrificed for the sake of cheap, mass-scale production.

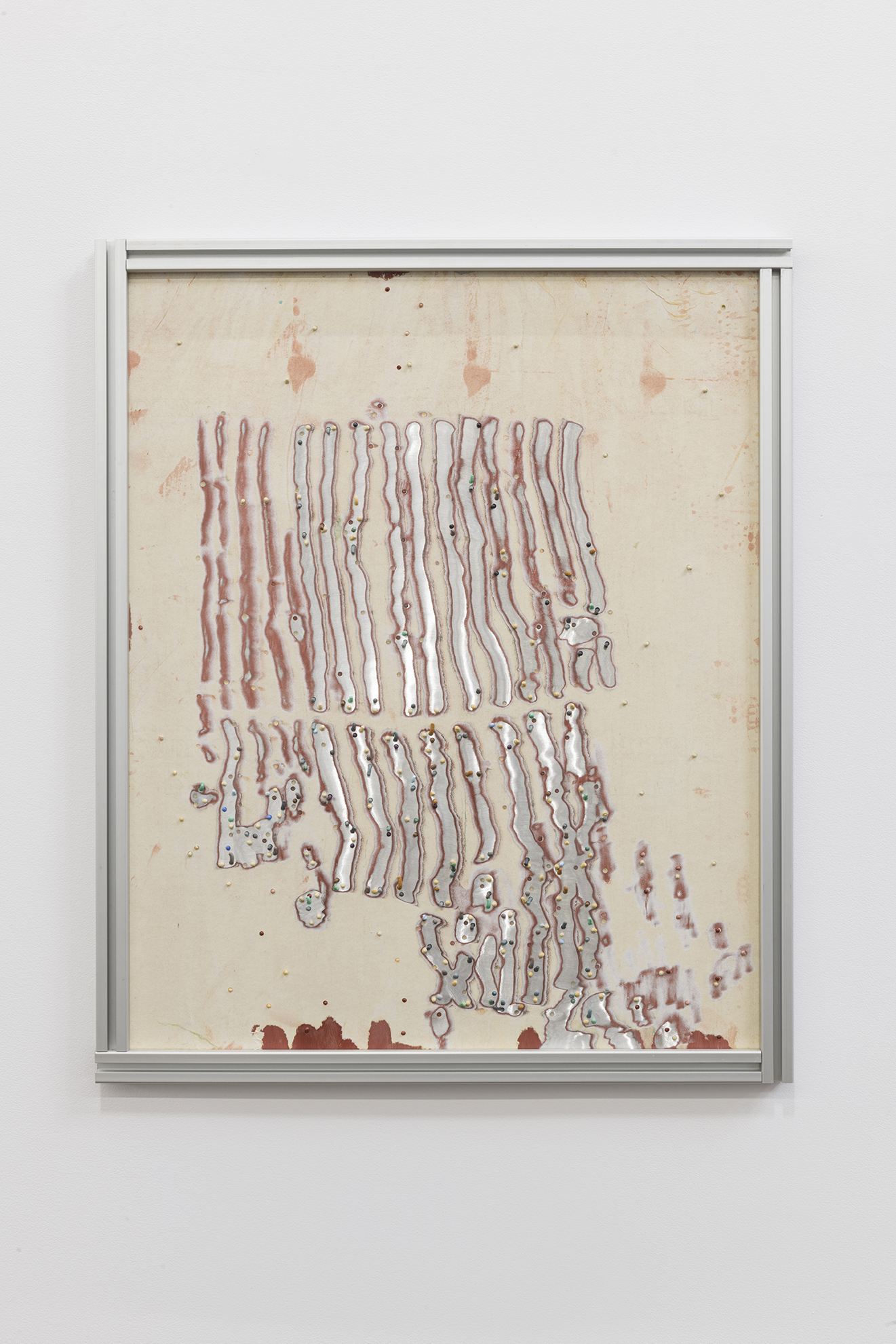

For his new project, Enrique Radigales has created a series of paintings inspired by heat maps, the free online software that highlights the parts of the screen where (for example) the cursor has spent the most time, or where most clicks have taken place. The results are images that might remind us, at first glance, of both abstract paintings and landscapes. The name given to this technology, i.e. "eyetracking", is telling: the "eye" is the gaze of the interpreting viewer, while the "tracking" follows its every movement. The term indicates that this is a physical space which thus allows (or gives rise to) exploration, a dérive or "drift". Poor design is a deviation, swerving off the beaten track, but it is also a change from the predictable or calculated.

The paintings by Radigales are dérives, wanderings: to paint is to make constant decisions which, in turn, depend on the technology of the paint itself. But these works are also created instinctively, on the fly; accidents happen and unforeseen problems get solved...

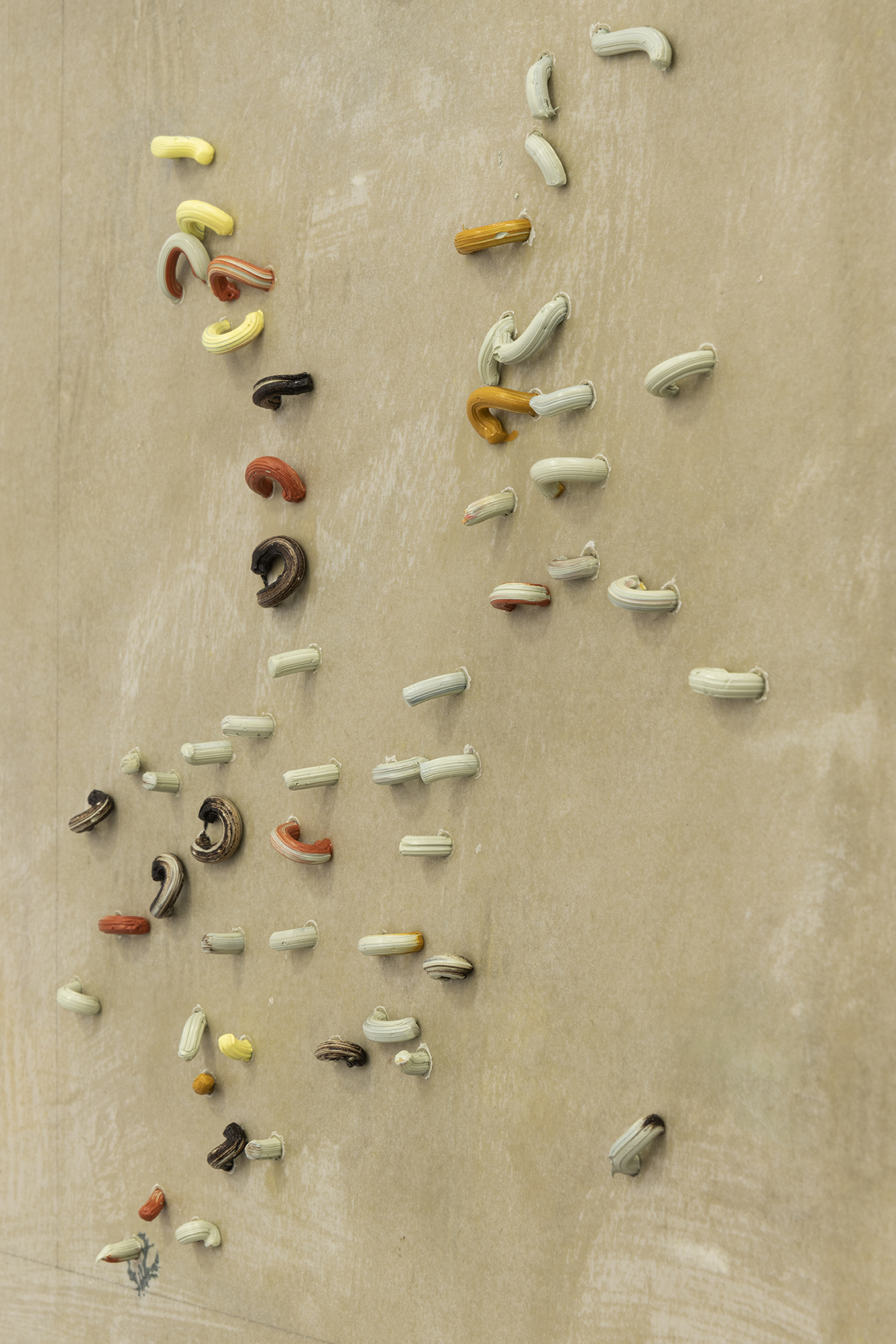

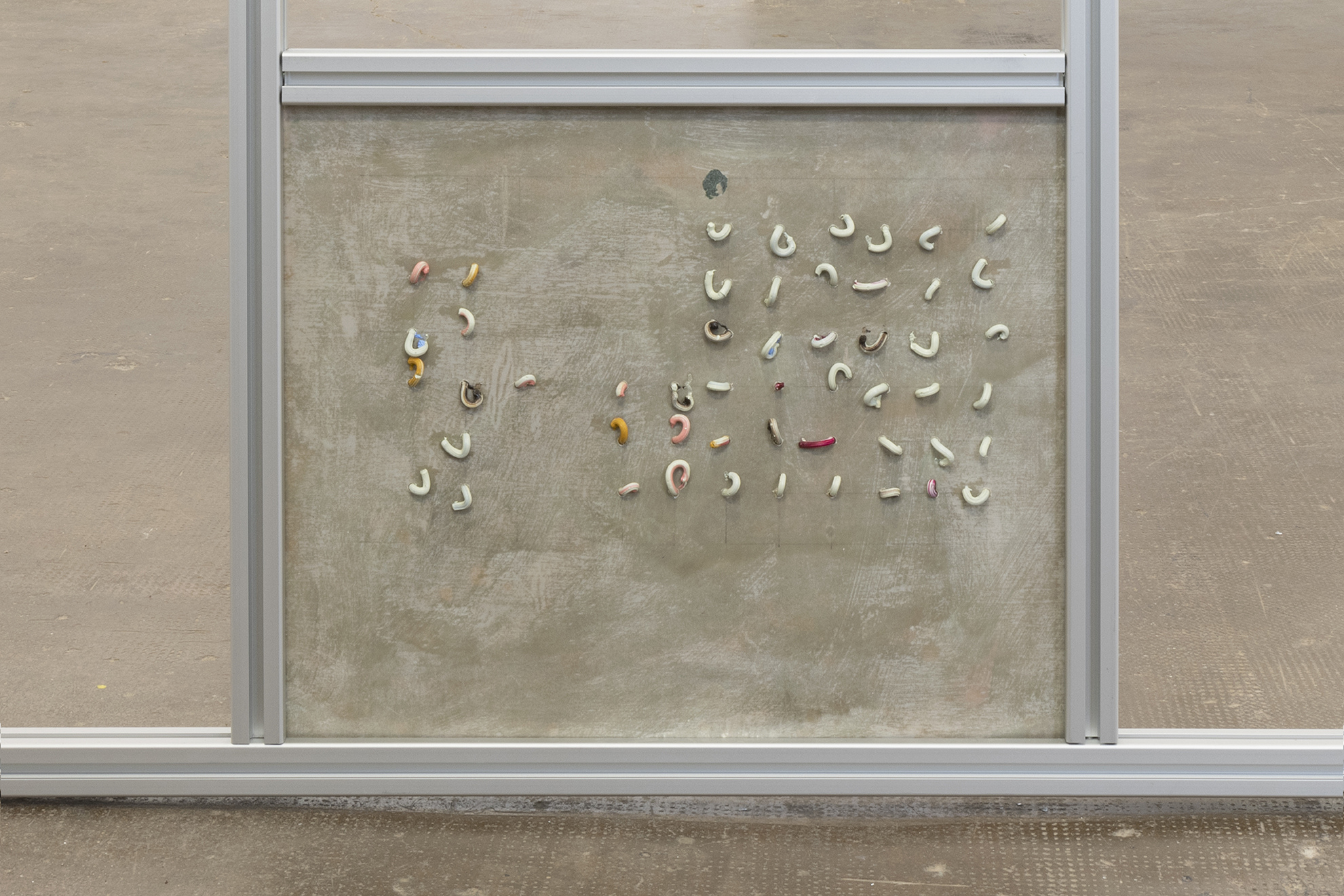

The paintings in this project can be divided into two speeds: some are fast, painted on metal (because the process can be assisted by electric machinery), while some are slow, on wood, in which the work is necessarily gradual and delicate. The same thing happens with painterly materials that have different drying times. The artist links them with digital effects: he zooms in for the oil on wood, and zooms out for the acrylic on metal. Or, in other words, macro and micro. It's the same with the tools used (i.e. fine paintbrushes or angle grinders) and the labour (completely manual or mechanical). The result, therefore, also differs in terms of the size and weight of the works.

The drying time is when we get the chance to reflect and meditate about what we want (or rather, specifically, what the artist wants). For Radigales, the technical aspect is fundamental in his creative process. The effects of these technological processes add elements to the work, such as the materials' needs for hydration or the effects of extrusion. Furthermore, the random events and experiences are different each time, thus shaping a distinct end result. The work is also contingent upon the artist's familiarity with the various tools he uses.

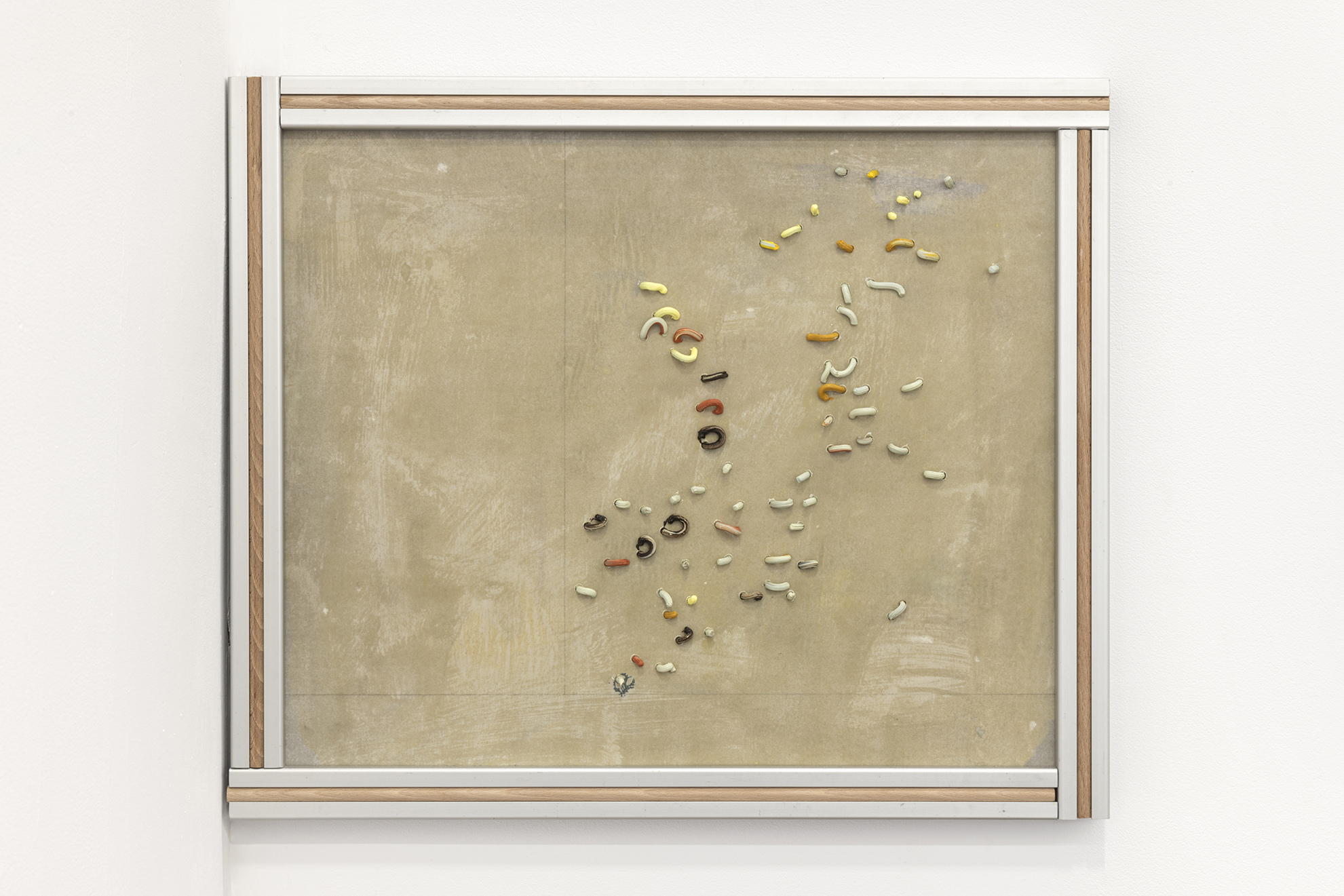

In order to appreciate all these processes in the gallery setting, the paintings have to be shown in a way so that the visitor can see both sides of them. They are framed within aluminium structures, custom-built with three distinct inspirations in mind: firstly, they are like a stylised version of the looms from the first Industrial Revolution; secondly, they depict the way computer screens are divided into frames (a largely defunct HTML technology, on the verge of obsolescence); and finally, they are made of a material that symbolises today's pre-fabricated construction methods. They are also mobile, much like the artist's life experience. The works are on display now at Galería Alegría in Barcelona, where the artist has returned after his time spent in Zaragoza and Madrid.

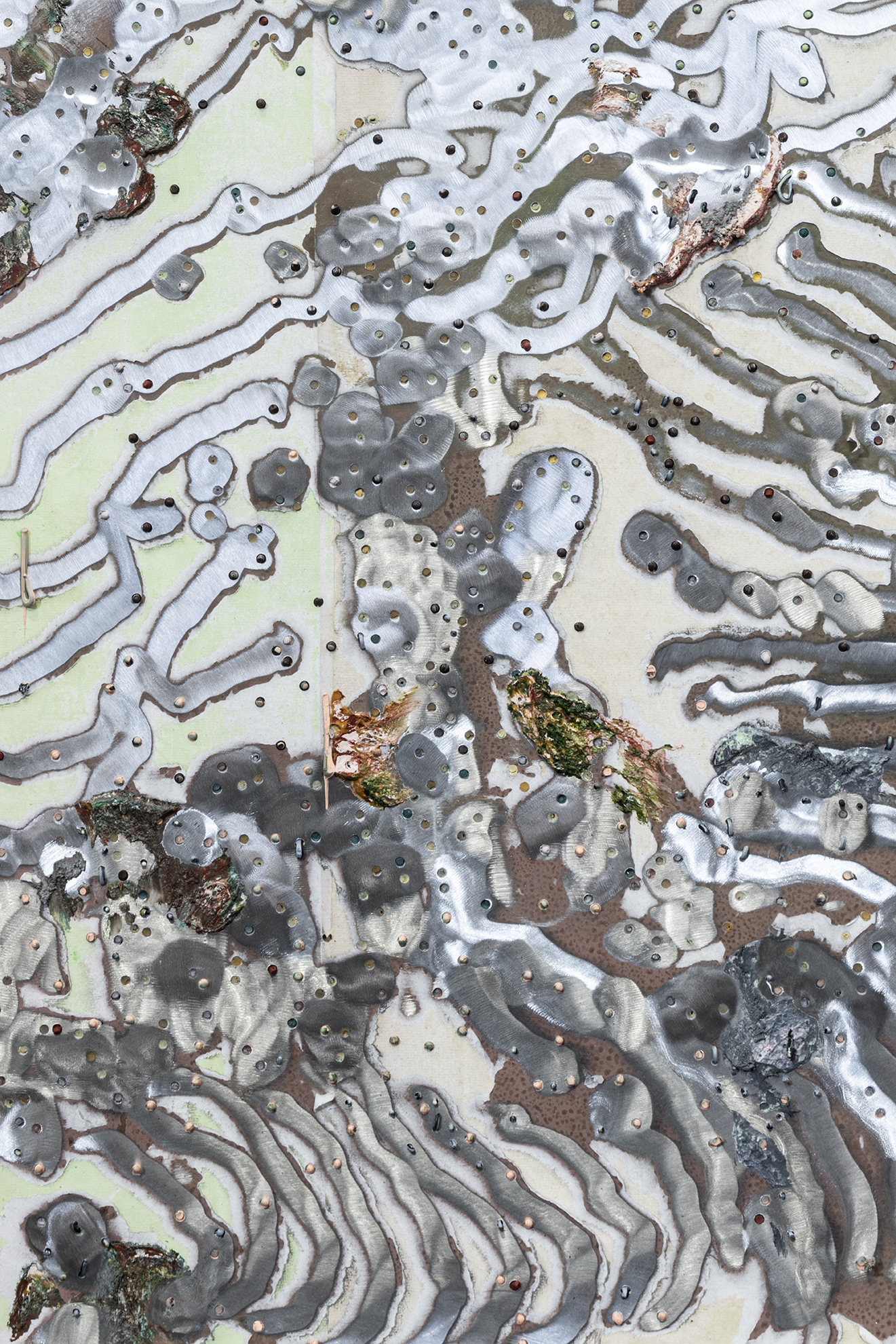

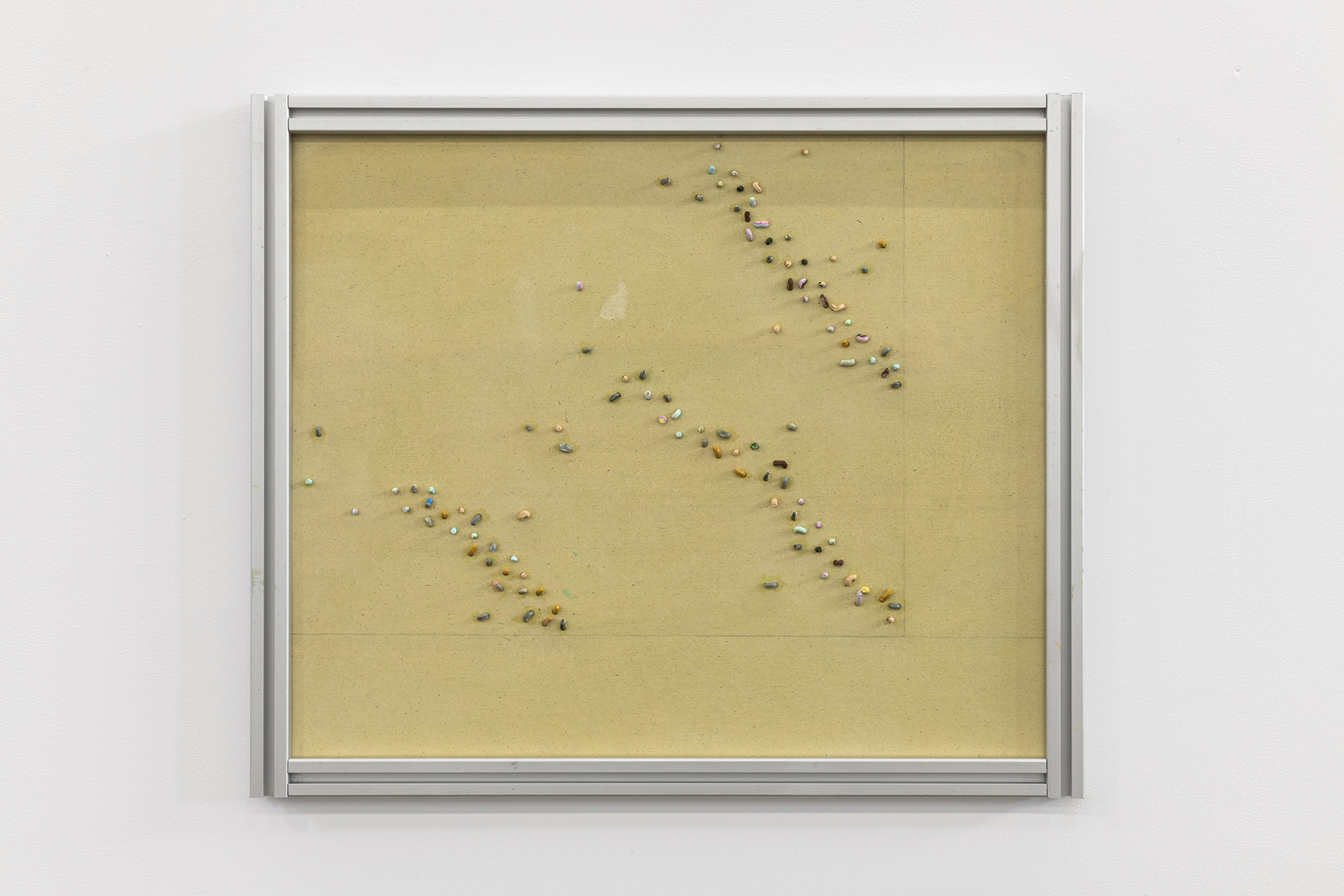

Just like in the windows on our computer screens, these images overlap and lay on top of one another. They cover each other up, they expose each other. They blend together, giving rise to brand-new images. These paintings are the result of the artist's life and intellectual experience. Placed on top of them are large-scale photographs which, when blown up as much as possible, reveal microscopic sculptures, built from physical elements that encapsulate the artist's whole creative process.

In those images we see true totems, built from a mix of painterly practice as altered by psycho-tools, which is one/another way of accessing this particular field of praxis. They combine physical elements, stripped from the painted surface by mechanical means (with an angle grinder, to be specific), and loose waste. All of this is accompanied by a microdosing of psychotropic substances during the making process. Unlike painting, which is an intellectual and manual exercise, these are photographs, collages constructed by computer. They play around with the fundamental duplicity of the photograph, i.e. that it is a documentary object, but also a falsification. Just like the memory, just like mental images.

The act of painting is a constant battle against your own limitations, and against the burden of tradition and history. To break free from these restraints, the artist has taken psychotropic substances, under the close supervision of a psychiatrist. Again, this reflects part of the artist's life history, i.e. his consumption of substances, at a certain age, in that end-of-century Barcelona.

Eyetracking is a project that summarises and encompasses the artistic practice of Enrique Radigales, taking in the landscapes of his childhood all the way up to the modernity of the big city. It is both a private, inner journey and a physical one, at the same time. We witness the endless overlaying of distinct landscapes: they include the landscape made in the gallery, with his frame structures; the landscapes he paints, and the ones made by superimposing these paintings; the mental landscapes he recreates in photographs; and the landscape imprinted into the spectators as a result of all these ones, and more. This is eyetracking, in the sense of seizing "what the gaze has captured".

Joaquín García Martín